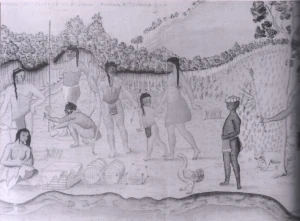

MARY ROWLANDSON was already the captive of a religious cult before the Natives of New England grabbed her during a raid in 1676, she just didn’t know it.  (Woodcut of Rowlandson’s kidnapping. Reprinted in Captive Selves, Captivating Others by Pauline Turner Strong

(Woodcut of Rowlandson’s kidnapping. Reprinted in Captive Selves, Captivating Others by Pauline Turner Strong

Like Mary, I was born into a similar updated version of this cult—three hundred years later (at least burning/hanging witches stopped, for now).

By the time of her abduction during KING PHILIP’S WAR, the beginning of the real end for the sovereignty of New England’s Native People, Mary had lived her forty years in the religious movement called Puritan, so-called by their peers. Puritans professed to lead a life of purity, a life of pure thoughts, a life dedicated to finishing what the Protestant Reformation had started the century before—eliminate any residual popish rituals in the Church of England. Of course, many Englishmen liked their Church just the way it was.

So, Puritans immigrated to America starting with the Mayflower in 1620 to not only escape persecution, but to build a New Jerusalem in a new, pure environment, free to rule their city-on-a-hill without any pesky King or Archbishops to interfere.

Soon after, their hero, OLIVER CROMWELL, seized power with the help of his New Model Army and lobbed off King Charles’ head, but ten years later, Cromwell was dead, and the throne was restored to Charles’ son. In spite of it all, the Puritans of New England forged ahead, and by this time (1660) they outnumbered their Native neighbors by at least three to one. European diseases had killed many Natives, who some ethnographers think numbered 144,000 in New England circa 1600, shrinking to a mere 15,000 by 1620. Entire villages…gone (Page 174).

Puritans modeled their Churches of Christ (Winthrop 264) after the Christian church of the first century following the death of Jesus (at least their vision of what the church was like), a primitive Christianity based on the letters of the Apostles in the Geneva Bible, the preferred version for the English dissenters.

My Church of Christ is a modified version, but still sticking to their patriarchal, misogynistic attempt at a first century model. Of course, any generality is fraught with danger, but a large block of the Republican Party traditionally votes for candidates that favor dictating moral behavior that melded into that old tune of what came to be called manifest destiny.

After all, God is on their side.

Like me, Mary was born into this cult. Mary’s father, Puritan John White, brought his family to New England in 1638 during the Great Migration, when Mary was three, and had moved through the forest to Lancaster about forty miles from Boston around 1652, which at that time was the “vast and desolate wilderness” (Lincoln 132). Mary experienced life through the Bible-tinted glasses of a New England Puritan, a life that was conditioned from birth to believe only the Saints (Puritans) would inherit the Kingdom of God, if they measured up right.

Puritans constantly searched “for clues to God’s purposes” (Fischer 125), and the Natives were obviously sent by the Devil to test their faith. The Puritan Priest, INCREASE MATHER, wholeheartedly agreed with his predecessor and father-in-law, John Cotton. “The conversion of the Indians is not to be expected […] before the conversion of the Jewish Nation” (Mather 4). Cryptic scriptures were dredged up to justify the wholesale slaughter of innocent Native women and children. “I will bring a sword upon you, that shall avenge the quarrel of the Covenant, Leviticus 26:25” (Mather 1). The Bible was their creed, a malleable text to justify their every edict or law, then as now.

In the course of researching my MAYFLOWER genealogy, I stumbled across THE STORY OF MARY BEING WEETAMOO’S SLAVE. In fact, I don’t remember any American history class I took that talked much about the 17th century. The nice Thanksgiving picture with Indians and Pilgrims getting along would dissolve into the next big event—the American Revolution. Not much happened in between, right? Wrong.

The contrast between Weetamoo and Mary Rowlandson could not have been more stark. Weetamoo was born a beloved Queen in her community. Mary was born a wretched sinner and as a woman, a second-class citizen (Fischer 84). Weetamoo was a warrior, Mary was a homemaker (I’m not suggesting this is bad), and the list continues. In the Puritan world women carried then and now the burden of their sex causing the downfall of the entire human race, thanks to Eve’s dalliance with the snake in the Garden of Eden. This event is still taught as fact. And how about the planet being 6012 years old? What’s wrong with you scholars, can’t you add up all the begets in the Bible’s Old Testament?

I was told to ignore what I learned at school. No dancing, no swimming with the opposite sex, no sex for fun, in fact, don’t even mention the word sex. No musical instruments in church. No asking questions.

Puritans censor a wide-ranging selection of words and artistic endeavors, such as literature, art, film, and skinny-dipping.

Mary was unable to see Weetamoo and Natives, in general, as human beings. The Native propensity for nakedness shocked Puritans. Adam and Eve in Genesis were ashamed of their nakedness. Why not these Natives? Native People were wolves, heathens—wicked creatures of the night. Mary didn’t see Weetamoo’s religion or its rituals. She didn’t see their villages as communities, but rather dens of wolves. The natural environment was not a rich, ancient forest, but a “vast and howling wilderness” (Lincoln 134). Puritans, like many Europeans, believed “unicorns lived in the hills, […] mermaids swam in waters, […] tritons played in Casco Bay,” and of course, witches must be burned (Fischer 125). As late as the 18th century, artistic drawings suggest Europeans in general “still had a hard time actually seeing Indians” (Page Centerfold).  (“Drawing of the Savages of Several Nations.” Alexandre de Batz (1735). Reproduced In The Hands of Great Spirit.” Jake Page.)

(“Drawing of the Savages of Several Nations.” Alexandre de Batz (1735). Reproduced In The Hands of Great Spirit.” Jake Page.)

Mary was eventually ransomed back to her husband and reunited with two of her children. One daughter died during her captivity, but Weetamoo (her children had already died) and what was left of her family died soon after. The Puritans stuck Weetamoo’s head on a pole at Taunton, the site of her ancient homeland. At seeing this head, members of her tribe in the stockade sobbed, “Our Queen…our Queen is dead” (Mather 137).

Mary returned to her Puritan life and was encouraged to write her captivity story, most likely by Mather, who may have written the introduction, perhaps in part to stop any nasty rumors of her defilement (read sex) from the hands of any “savages,” a common problem for any woman returning to Puritan communities from captivity (Strong 101), although rape of English women by Native men was an uncommon occurrence. Of course, if Mary willingly had sexual relations with a Native man, she would have been branded or worse.

MARY’S BOOK also provided a fresh text for Mather and friends to use in the pulpit as propaganda against Native People.  Sometimes even the Bible didn’t frighten the flock as well as a good, scary story in their own backyard, using fear to control people—straight out of the Puritan-like strategy book. Captivity narratives became all the rage after Mary published her book.

Sometimes even the Bible didn’t frighten the flock as well as a good, scary story in their own backyard, using fear to control people—straight out of the Puritan-like strategy book. Captivity narratives became all the rage after Mary published her book.

Now as then, the struggle to think clearly continues.

WORKS CITED

Dillaway, Newton, ed. The Gospel of Emerson. Mass: The Montrose P, 1949.

Winthrop, John. “On Liberty.” 1645. Constitution Society.5 Aug 2008 http://www.constitution.org/

Lincoln, Charles H., ed. Narratives of the Indian Wars 1675 – 1699. New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1913.

Mather, Increase. A Brief History of the Warr with the Indians in New-England (1676). Ed. Paul Royster. Nebraska: U of Nebraska, 2006. 8 Aug 08

Page, Jake. In The Hands of the Great Spirit: The 20,000 -Year History of American Indians. USA: Free Press, 2003.

Philbrick, Nathaniel. Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War. USA: Penguin, 2007.

Strong, Pauline Turner. Captive Selves, Captivating Others: The Politics and Poetics of Colonial American Captivity Narratives. USA: Westview P, 1999.

More information and links: http://www.conradreeder.com/TheCaptive.htm

Conrad “Connie” Reeder was born in Columbus, Ohio. BA Liberal Arts and a MFA in Film, Theater, & Communication Arts with a concentration in Playwriting.

The Captive is a dramatic play in two acts.

Contact: conradreeder@gmail.com

© All Rights Reserved